Teaching a yoga class for the aging was a given for this year’s Telluride Yoga Festival, and it happens to be my favorite kind of class to teach. Blessed to have the opportunity to teach a second class, I was asked to submit a “juicy” description, something that might attract a lot of participants.

Juicy? I wasn’t quite sure what this meant, but what I did know, is that the Huffington Post had just published my article titled 50 Shades of Namaste, so I submitted a class idea with the same title.

For obvious reasons, the class description had nothing to do with the content of my article. Thank goodness. Since my article was published, I’ve received email inquiries asking me to discuss my expertise in the subject of inflicting pain for pleasure. I’ve had to make it clear several times, that my area of authority is in yoga, not whips and chains!

Shifting the meaning of the title to something that would be of value at a yoga festival, I came up with the following description:

“Yoga in America is not black and white. We have numerous styles, varied approaches, and sometimes, conflicting instructions. How can we know what’s best? We’ve all heard the cues to listen to our body and do what feels good, but there isn’t always a clear distinction between the sensations of pleasure and pain. In this class we will discover how and why our bodies talk, and learn ways to enhance our mind-body communication so we can safely, and pleasurably navigate the gray areas of modern yoga practices.”

Everyone wants to do yoga the right way. So, I began by asking the class if there was any uncertainty as to how to practice a particular yoga pose. I didn’t expect this, but one man started by asking how he could get his students with poor posture to pull their shoulders back in a pose. That question paved the way for an anatomical synopsis of the shoulder joint, and what actually happens when we “pull our shoulders back.”

While the concept seems as simple as squeezing the scapulae (shoulder blades) together, there is a lot more to consider. I went on to explain how poor posture and muscle imbalance developed over time takes just as much time to reverse, and to expect perfect posture in one class is a misnomer. Certain poses that require the shoulders to be pulled back-but are prevented from doing so because of a tight chest, need to be looked at differently as to prevent unnecessary torque and misalignment of the shoulder joint, especially when the arms are bearing weight.

Other questions involved wrist placement in plank, knee position in revolved chair pose, and whether to tuck or untuck the tailbone in standing poses. When asked, my answers always started with, “it depends.”

During the next half hour, I discussed why it depends. The reasons are quite simple. No two styles of yoga are exactly the same, just as no two bodies that practice yoga are exactly the same. We might think deep down at the skeletal level, we are the same, but that is incorrect. The shape of our bones can greatly affect how we look and feel in a yoga pose, and that is a big factor in determining how and why it depends which way is the right way. When we do a yoga pose, two major elements come into play; our bones, and our muscles.

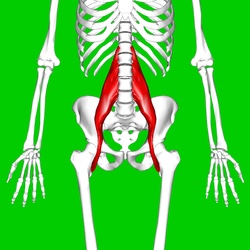

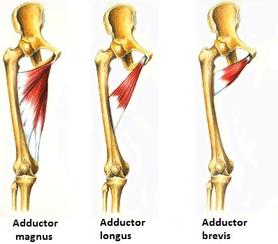

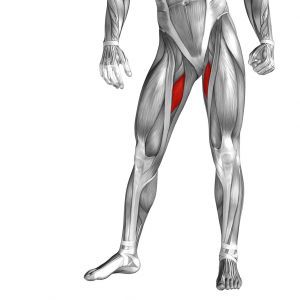

Referencing Paul Grilley, and his DVD, Anatomy for Yoga, I discussed the concept of compression and tension. Compression is a term that explains a permanent limitation due to bones blocking movement. For example, if you straighten your arm, you eventually come to a stop. This is because the bones of your humerus and ulna have locked in place due to a bony protrusion called the olecranon process, and nothing short of an accident will move them beyond that range of motion. This is an example of compression. It seems like a welcome protective mechanism, but this can happen in other areas of our bodies that are generally built to have more movement, such as the shoulder and the hip joint.

I went on to discuss the anatomy of the hip and shoulder joint, relative to the concept of compression. For example, the hip is a ball and socket joint. Sometimes the ball part of the joint is bigger than average, or sometimes the socket part of the joint is deeper than average. In either instance, this can have a tremendous affect on how much or little the hip can move, regardless of how flexible or inflexible the connective tissue around the hip joint may be. Apply that to yoga, and we understand that no amount of stretching will change the shape of our bones. If bone on bone compression has been met, in the case of the ball bumping into the socket, there is no going beyond that point.

Tension is different. Tension is muscle tightness, and that can be overcome. You know this to be true when you go to yoga, and at the end of the class you are a little bit more limber. After years of practice, you might even be able to touch your toes, etc.

Making clear that if certain movement patterns or limitations are due to compression, nothing can be done about it. If certain movement patterns or limitations are due to tension, we can work a little harder to overcome it. We all have a combination of both tension and compression happening in our bodies.

So, how can we tell which is which? I discussed how our bodies communicate with our brains.

We all have an innate sense of body awareness, and this is referred to as kinesthetic intelligence. This awareness is communicated through proprioception, which is the feedback sent from our muscles to our brain. If we need to make changes in our posture, our brain sends the message to our muscles to move.

Incidentally, the words proprioception and appropriate share the same root word, and that is proprius, meaning: one’s own. Proprioception can alert us when we might be doing a pose inappropriately, based on the feedback we receive from our body. Kinesthetic intelligence is the movement we execute to make the pose appropriate for our body.

We did a little practice to experience these mechanisms at work. We stood on one foot with our eyes closed. Proprioception told us when we were about to fall over, our kinesthetic intelligence moved our bodies into position so we wouldn’t fall over. This type of communication happens all the time, whether we are aware of it or not.

Sometimes, due to injury and pain, the messages we receive from our bodies can be misinterpreted. I discussed the cycle of pain and pleasure, commonly understood as runner’s high, but also experienced in yoga. Neurotransmitters such as dopamine reward our bodies after a bout of pain. (I had to bring in a discussion of pain, after all, this was 50 Shades of Namaste!) However, I pleaded with the class to not get caught up in a false perception of what is good for us because of a flood of feel-good chemicals brought on by a bout of pain. I did find it it ironic that a newly discovered neurotransmitter was aptly named anandamide. For those of you who don’t know, ananda is the Sanskrit word for bliss. We really don’t have to hurt in order to feel good. If you want to read more about the pain and pleasure cycle in yoga, read my article. For the record, I am not an advocate for pain.

As we proceeded to do some yoga, I quoted Leslie Kaminoff, author of Yoga Anatomy, the book we use in my yoga teacher training courses. Kaminoff says,

“Asanas [yoga poses] don’t have alignment, people have alignment. There is no universally correct alignment, only what is correct for the individual.”

I love this concept, because as a yoga teacher, it is easy to forget there isn’t a universal way to teach a yoga pose. It is an excellent reminder of how we are all built so differently. Honoring the individual, not some by-the-book ideal of a pose, is very important.

The ongoing question buzzing around the yoga community has always been, “Which way is the correct way to do a pose?” I’m confident to have made my point that it really depends on who is doing the pose. Yoga is a lifelong journey with no quick fix or immediate answers. Each and every time we practice is a little bit different. Knowing what we need “right now” takes time and attention, but it is possible for both teachers, and students to understand.

In addition to Paul Grilley’s DVD, and Leslie Kaminoff’s book, Yoga Anatomy, I also recommend the book, Your Body, Your Yoga, by Bernie Clark.